You are reading out of date documentation. Please see the latest docs.

When you started using PyXLL you probably discovered how easy it is to register a Python function in Excel. To improve efficiency and reduce the chance of errors, you can also specify what types the arguments to that function are expected to be, and what the return type is. This information is commonly known as a function’s signature. There are three common ways to add a signature to a function, described in the following sections.

The most common way to provide the signature is to provide a function signature as the first

argument to xl_func:

from pyxll import xl_func

from datetime import date, timedelta

@xl_func("date d, int i: date")

def add_days(d, i):

return d + timedelta(days=i)

When adding a function signature string it is written as a comma separated list of each argument type followed

by the argument name, ending with a colon followed by the return type. The signature above specifies that the

function takes two arguments called d, a date, and i, and integer, and returns a value of type date.

You may omit the return type; PyXLL automatically converts it into the most appropriate Excel type.

Adding type information is useful as it means that any necessary type conversion is done automatically, before your function is called.

Type information can also be provided using type annotations in Python 3. This example shows how you pass dates to Python functions from Excel using type annotations:

from pyxll import xl_func

from datetime import date, timedelta

@xl_func

def add_days(d: date, i: int) -> date:

return d + timedelta(days=i)

Internally, an Excel date is just a floating-point a number. If you pass a

date to a Python function with no type information then that argument will

just be a Python float when it is passed to your Python function. Adding a

signature removes the need to convert from a float to a date in every

function that expects a date. The annotation on your Python function (or the

signature argument to xl_func) tells PyXLL and Excel what

type you expect, and the the conversion is done automatically.

The final way type information can be added to a function is by using specific argument and return type

decorators. These are particularly useful for more complex types that require parameters, such as

NumPy arrays and Pandas types. Parameterized types can be specified

as part of the function signature, or using xl_arg and xl_return.

For example, the following function takes two 1-dimensional NumPy arrays, using a function signature:

from pyxll import xl_func

import numpy as np

@xl_func("numpy_array<ndim=1> a, numpy_array<ndim=1> b: var")

def add_days(a, b):

return np.correlate(a, b)

But this could be re-written using xl_arg as follows:

from pyxll import xl_func, xl_arg

import numpy as np

@xl_func

@xl_arg("a", "numpy_array", ndim=1)

@xl_arg("b", "numpy_array", ndim=1)

def add_days(a, b):

return np.correlate(a, b)

Several standard types may be used in the signature specified when exposing a Python worksheet function. These types have a straightforward conversion between PyXLL’s Excel-oriented types and Python types. Arrays and more complex objects are discussed later.

Below is a list of these basic types. Any of these can be specified as an argument type or return type in a function signature.

PyXLL type |

Python type |

|---|---|

bool |

|

datetime |

|

date |

|

float |

|

int |

|

object |

|

rtd |

|

str |

|

time |

|

unicode |

|

var |

|

xl_cell |

|

range |

Excel Range COM Wrapper [7] |

Notes

The var type can be used when the argument or return type isn’t fixed.

Using the strong types has the advantage that arguments passed from Excel will get coerced

correctly. For example if your function takes an int you’ll always get an int and there’s no need to do

type checking in your function. If you use a var, you may get a float if a number is passed to your

function, and if the user passes a non-numeric value your function will still get called so you need to check the type

and raise an exception yourself.

If no type information is provided for a function it will be assumed that all arguments and the return

type are the var type. PyXLL will do its best to perform the necessary conversions, but providing

specific information about typing is the best way to ensure that type conversions are correct.

Specifying xl_cell as an argument type passes an XLCell instance to your function instead

of the value of the cell. This is useful if you need to know the location or some other data about the cell

used as an argument as well as its value.

New in PyXLL 4.4*

The range argument type is the same as xl_cell except that instead of passing an XLCell

instance a Range COM object is used instead.

The default Python COM package used is win32com, but this can be changed via an argument to the range

type. For example, to use xlwings instead of win32com you would use range<xlwings>.

See Array Functions for more details about array functions.

Ranges of cells can be passed from Excel to Python as a 1d or 2d array.

Any type can be used as an array type by appending [] for a 1d array or [][] for a 2d array:

from pyxll import xl_func

@xl_func("float[][] array: float")

def py_sum(array):

"""return the sum of a range of cells"""

total = 0.0

# 2d array is a list of lists of floats

for row in array:

for cell_value in row:

total += cell_value

return total

A 1d array is represented in Python as a simple list, and when a simple list is returned to Excel it will be returned as a column of data. A 2d array is a list of lists (list of rows) in Python. To return a single row of data, return it as a 2d list of lists with only a single row.

When returning a 2d array remember that it* must* be a list of lists. This is

why you woud return a single a row of data as [[1, 2, 3, 4]], for example.

To enter an array formula in Excel you select the cells, enter the formula

and then press Ctrl+Shift+Enter.

Any type can be used as an array type, but float[] and float[][] require the least marshalling between Excel and

python and are therefore the fastest of the array types.

If you a function argument has no type specified or is using the var type, if it is passed a range of data

that will be converted into a 2d list of lists of values and passed to the Python function.

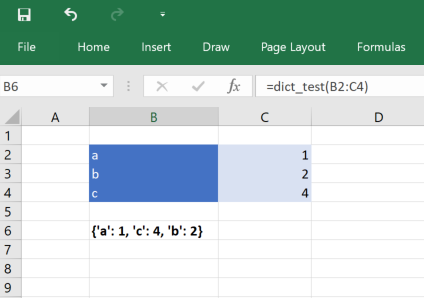

Python functions can be passed a dictionary, converted from an Excel range of values.

Dicts in a spreadsheet are represented as a 2xN range of keys and their associated values.

The keys are in the columns unless the range’s transpose argument (see below) is true.

The following is a simple function that accepts an dictionary of integers keyed by strings. Note that

the key and value types are optional and default to var if not specified.

@xl_func("dict<str, int>: str") # Keys are strings, values are integers

def dict_test(x):

return str(x)

The dict type can be parameterized so that you can also specify the key and value types, and some other

options.

dict, when used as an argument type

dict<key=var, value=var, transpose=False, ignore_missing_keys=True>key Type used for the dictionary keys.

value Type used for the dictionary values.

transpose

- False (the default): Expect the dictionary with the keys on the first column of data and the values on the second.

- True: Expect the dictionary with the keys on the first row of data and the values on the second.

- None: Try to infer the orientation from the data passed to the function.

ignore_missing_keys If True, ignore any items where the key is missing.

dict, when used as an return type

dict<key=var, value=var, transpose=False, order_keys=True>key Type used for the dictionary keys.

value Type used for the dictionary values.

transpose

- False (the default): Return the dictionary as a 2xN range with the keys on the first column of data and the values on the second.

- True: Return the dictionary as an Nx2 range with the keys on the first row of data and the values on the second.

order_keys Sort the dictionary by its keys before returning it to Excel.

To be able to use numpy arrays you must first have installed the numpy package..

You can use numpy 1d and 2d arrays as argument types to pass ranges

of data into your function, and as return types for returing for array

functions. A maximum of two dimensions are supported, as higher dimension

arrays don’t fit well with how data is arranged in a spreadsheet. You can,

however, work with higher-dimensional arrays as Python objects.

To specify that a function should accept a numpy array as an argument or as

its return type, use the numpy_array, numpy_row or numpy_column

types in the xl_func function signature.

These types can be parameterized, meaning you can set some additional options when specifying the type in the function signature.

numpy_array<dtype=float, ndim=2, casting='unsafe'>dtype Data type of the items in the array (e.g. float, int, bool etc.).

ndim Array dimensions, must be 1 or 2.

casting Controls what kind of data casting may occur. Default is ‘unsafe’.

'unsafe' Always convert to chosen dtype. Will fail if any input can’t be converted.

'nan' If an input can’t be converted, replace it with NaN.

'no' Don’t do any type conversion.

numpy_row<dtype=float, casting='unsafe'>dtype Data type of the items in the array (e.g. float, int, bool etc.).

casting Controls what kind of data casting may occur. Default is ‘unsafe’.

'unsafe' Always convert to chosen dtype. Will fail if any input can’t be converted.

'nan' If an input can’t be converted, replace it with NaN.

'no' Don’t do any type conversion.

numpy_column<dtype=float, casting='unsafe'>dtype Data type of the items in the array (e.g. float, int, bool etc.).

casting Controls what kind of data casting may occur. Default is ‘unsafe’.

'unsafe' Always convert to chosen dtype. Will fail if any input can’t be converted.

'nan' If an input can’t be converted, replace it with NaN.

'no' Don’t do any type conversion.

For example, a function accepting two 1d numpy arrays of floats and returning a 2d array would look like:

from pyxll import xl_func

import numpy

@xl_func("numpy_array<float, ndim=1> a, numpy_array<float, ndim=1> b: numpy_array<float>")

def numpy_outer(a, b):

return numpy.outer(a, b)

The ‘float’ dtype isn’t strictly necessary as it’s the default. If you don’t want to set the type parameters in

the signature, use the xl_arg and xl_return decorators instead.

PyXLL will automatically resize the range of the array formula to match the returned data if you specify

auto_resize=True in your py:func:xl_func call.

Floating point numpy arrays are the fastest way to get data out of Excel into Python. If you are working

on performance sensitive code using a lot of data, try to make use of numpy_array<float> or

numpy_array<float, casting='nan'> for the best performance.

See Array Functions for more details about array functions.

Pandas DataFrames and Series can be used as function arguments and return types for Excel worksheet functions.

When used as an argument, the range specified in Excel will be converted into a Pandas DataFrame or Series as specified by the function signature.

When returning a DataFrame or Series, a range of data will be returned to

Excel. PyXLL will automatically resize the range of the array formula to

match the returned data if auto_resize=True is set in xl_func.

The following shows returning a random dataframe, including the index:

from pyxll import xl_func

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

@xl_func("int rows, int columns: dataframe<index=True>", auto_resize=True)

def random_dataframe(rows, columns):

data = np.random.rand(rows, columns)

column_names = [chr(ord('A') + x) for x in range(columns)]

return pd.DataFrame(data, columns=column_names)

The following options are available for the dataframe and series argument and return types:

dataframe, when used as an argument type

dataframe<index=0, columns=1, dtype=None, dtypes=None, index_dtype=None>

indexNumber of columns to use as the DataFrame’s index. Specifying more than one will result in a DataFrame where the index is a MultiIndex.

columnsNumber of rows to use as the DataFrame’s columns. Specifying more than one will result in a DataFrame where the columns is a MultiIndex. If used in conjunction with index then any column headers on the index columns will be used to name the index.

dtypeDatatype for the values in the dataframe. May not be set with dtypes.

dtypesDictionary of column name -> datatype for the values in the dataframe. May not be set with dtype.

index_dtypeDatatype for the values in the dataframe’s index.

dataframe, when used as a return type

dataframe<index=None, columns=True>

indexIf True include the index when returning to Excel, if False don’t. If None, only include if the index is named.

columnsIf True include the column headers, if False don’t.

series, when used as an argument type

series<index=1, transpose=None, dtype=None, index_dtype=None>

indexNumber of columns (or rows, depending on the orientation of the Series) to use as the Series index.

transposeSet to True if the Series is arranged horizontally or False if vertically. By default the orientation will be guessed from the structure of the data.

dtypeDatatype for the values in the Series.

index_dtypeDatatype for the values in the Series’ index.

series, when used as a return type

series<index=True, transpose=False>

indexIf True include the index when returning to Excel, if False don’t.

transposeSet to True if the Series should be arranged horizontally, or False if vertically.

When passing large DataFrames between Python functions, it is not always necessary to return the full DataFrame

to Excel and it can be expensive reconstructing the DataFrame from the Excel range each time. In those cases you

can use the object return type to return a handle to the Python object. Functions taking the dataframe

and series types can accept object handles.

See Using Pandas in Excel for more information.

Not all Python types can be conveniently converted to a type that can be represented in Excel.

Even for types that can be represented in Excel it is not always desirable to do so (for example, and Pandas DataFrame with millions of rows could be returned to Excel as a range of data, but it would not be very useful and would make Excel very slow).

For cases like these, PyXLL can return a handle to the Python object to Excel instead of trying to convert the object to an Excel friendly representation. The actual object is held in PyXLL’s object cache until it is no longer needed. This allows for Python objects to be passed between Excel functions easily, without the complexity or possible performance problems of converting them between the Python and Excel representations.

For more information about how PyXLL can automatically cache objects to be passed between Excel functions as object handles, see Cached Objects.

As well as the standard types listed above you can also define your own argument and return types, which can then be used in your function signatures.

Custom argument types need a function that will convert a standard Python type to the custom type, which will then be passed

to your function. For example, if you have a function that takes an instance of type X,

you can declare a function to convert from a standard type to X and then use X as a type in your

function signature. When called from Excel, your conversion function will be called with an instance of the base

type, and then your exposed UDF will be called with the result of that conversion.

To declare a custom type, you use the xl_arg_type decorator on your conversion function.

The xl_arg_type decorator takes at least two arguments, the name of your custom type and the base type.

Here’s an example of a simple custom type:

from pyxll import xl_arg_type, xl_func

class CustomType:

def __init__(self, x):

self.x = x

@xl_arg_type("CustomType", "string")

def string_to_customtype(x):

return CustomType(x)

@xl_func("CustomType x: bool")

def test_custom_type_arg(x):

# this function is called from Excel with a string, and then

# string_to_customtype is called to convert that to a CustomType

# and then this function is called with that instance

return isinstance(x, CustomType)

You can now use CustomType as an argument type in a function signature. The

Excel UDF will take a string, but when your Python function is called the

conversion function will have been used invisibly to automatically convert

that string to a CustomType instance.

To use a custom type as a return type you also have to specify the conversion function from your custom type to a base type. This is exactly the reverse of the custom argument type conversion described previously.

The custom return type conversion function must be decorated with the xl_return_type decorator.

For the previous example the return type conversion function could look like:

from pyxll import xl_return_type, xl_func

@xl_return_type("CustomType", "string")

def customtype_to_string(x):

# x is an instance of CustomType

return x.x

@xl_func("string x: CustomType")

def test_returning_custom_type(x):

# the returned object will get converted to a string

# using customtype_to_string before being returned to Excel

return CustomType(x)

Any recognized type can be used as a base type. That can be a standard Python type, an array type or another custom type (or even an array of a custom type!). The only restriction is that it must resolve to a standard type eventually.

Custom types can be parameterized by adding additional keyword arguments to the conversion functions. Values for

these arguments are passed in from the type specification in the function signature, or using xl_arg

and xl_return:

from pyxll import xl_arg_type, xl_func

class CustomType2:

def __init__(self, x, y):

self.x = x

self.y = y

@xl_arg_type("CustomType2", "string", y=None)

def string_to_customtype2(x):

return CustomType(x, y)

@xl_func("CustomType2<y=1> x: bool")

def test_custom_type_arg2(x):

assert x.y == 1

return isinstance(x, CustomType)

Sometimes it’s useful to be able to convert from one type to another, but it’s not always convenient to have to determine the chain of functions to call to convert from one type to another.

For example, you might have a function that takes an array of var types, but some of those may actually be datetimes, or one of your own custom types.

To convert them to those types you would have to check what type has actually been passed to your function and then decide what to call to get it into exactly the type you want.

PyXLL includes the function get_type_converter to do this for you.

It takes the names of the source and target types and returns a

function that will perform the conversion, if possible.

Here’s an example that shows how to get a datetime from a var parameter:

from pyxll import xl_func, get_type_converter

from datetime import datetime

@xl_func("var x: string")

def var_datetime_func(x):

var_to_datetime = get_type_converter("var", "datetime")

dt = var_to_datetime(x)

# dt is now of type 'datetime'

return "%s : %s" % (dt, type(dt))